Leyla Soncul, University of Liverpool history student, draws on archives of the Liverpool Free Press to explore one of the radical media’s investigative triumphs

This little newspaper, run on a shoestring and staffed by part-timers in a tiny office, was responsible for investigating and breaking the news of a huge corruption scandal that ended with three prison terms for local councillors and business leaders.

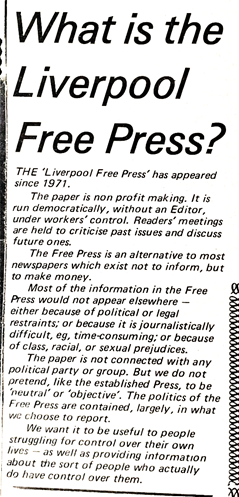

Liverpool Free Press (LFP) offered itself as an alternative to the mainstream media. It gave a voice to the declining city of Liverpool, rather than succumbing to ‘boomtown mentality’ which the Liverpool Echo and Daily Post indulged in. In a statement published in the paper titled ‘What is the Liverpool Free Press?’, determination to uncover information that was untouched by the lazy mainstream press was declared along with a desire to provide itself as a tool for disadvantaged communities to better understand who had control over their lives. Though sympathising with left-wing political groups, the Liverpool Free Press maintained independence from any particular party – it was anewspaper for the working-class community, free from propaganda, informing Liverpudlians of ‘news you’re not supposed to know.’

But if not born from a political party then where and why was it founded?

Liverpool Free Press emerged from a guerrilla newspaper, Pak-o-Lies, published to mock and expose the Echo and Daily Post. Brian Whitaker, Rob Rohrer and Chris Oxley, trained journalists from the Echo, along with the help of a friend who owned a small lithography press, Derek Massey, published two issues of Pak-o-Lies in 1971. The first of these addressed the Daily Post’s secret financial interest in the Liverpool Inner Motorway project plans of the 1960s.

The second issue blew the whistle on the Echo publishing disinformation on behalf of the Post Office in order to mislead strikers into returning to work. The highly inaccurate advertisement featured boldly on the front page claiming a union agreement had been made at national level. The Echo didn’t even charge for the deceptive advert.

This issue of Pak-o-Lies reached further than the intended audience of the staff at the Echo and Daily Post – 2,000 copies were sold. In the wake of this, the idea for Liverpool Free Press flourished. The plan was to create a newspaper which was less of a direct attack on mainstream press and more of a serious alternative, not dissimilar from Leeds Other Paper. (Though it did continue to expose the Echo and Post, and Pak-o-Lies continued as a feature for a short time in LFP’s early issues).

LFP also had a dedicated ‘Informer’ section which included columns on local music, theatre, and social clubs as well as ‘that traditional Liverpool pastime – drinking.’ This boosted the appeal of LFP as the growing localism meant alternative culture needed a space to provide updates and contact information, particularly as there was a division between this alternative culture and the culture of the establishment LFP and other community newspapers of this time worked as social media does today.

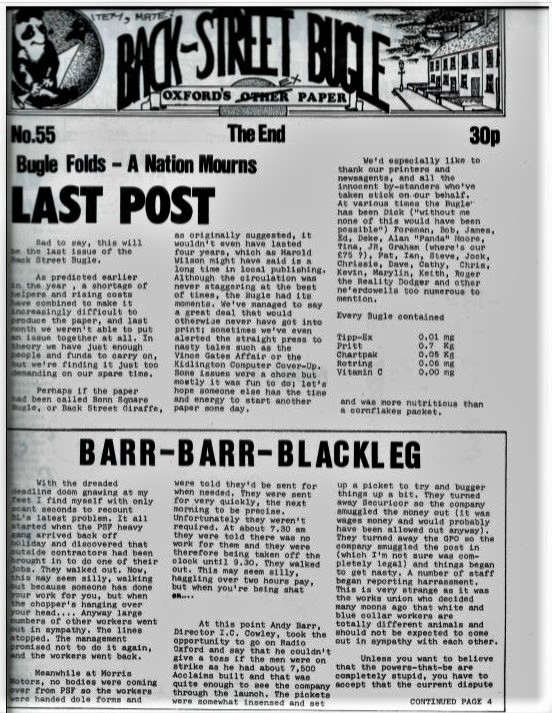

Essential to the publication was lithography printing. A large lithography press was sourced which LFP rented alongside Big Flame and the Merseyside Women’s Paper making it cheap and relatively easy. Eventually, LFP also manged to secure an office in a room, rent free, above the radical bookshop News From Nowhere. Much like Oxford’s Back Street Bugle and other alternative newspapers, LFP relied on a worker co-operative to sustain itself and radical bookshops also acted as important points of distribution. Though the core founders of LFP were trained journalists, their refusal to utilise many advertisements meant profits were low (if any) so they had to hold down full-time jobs along-side their writing. LFP also relied on input from non-professional writers who would chip in, here and there, to help out.

From here, the motivation which sustained the paper’s 7-year publication was a genuine desire to carry out proper investigative journalism – the kind which was near impossible to do under the mainstream local press at the time. These newspapers were far too busy meeting deadlines and filling spaces. This perhaps explains why the LFP was much more sporadic with their publications, only printing issues when they felt they had stories worth covering.

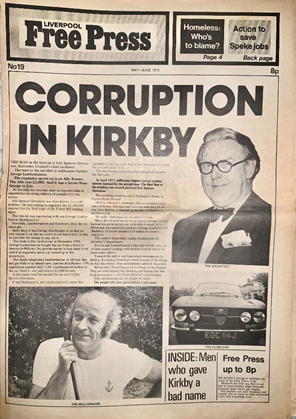

The corruption scandal in Kirkby 1976 following the housing crisis was amongst the LFP’s most successful and influential pieces of investigative journalism.

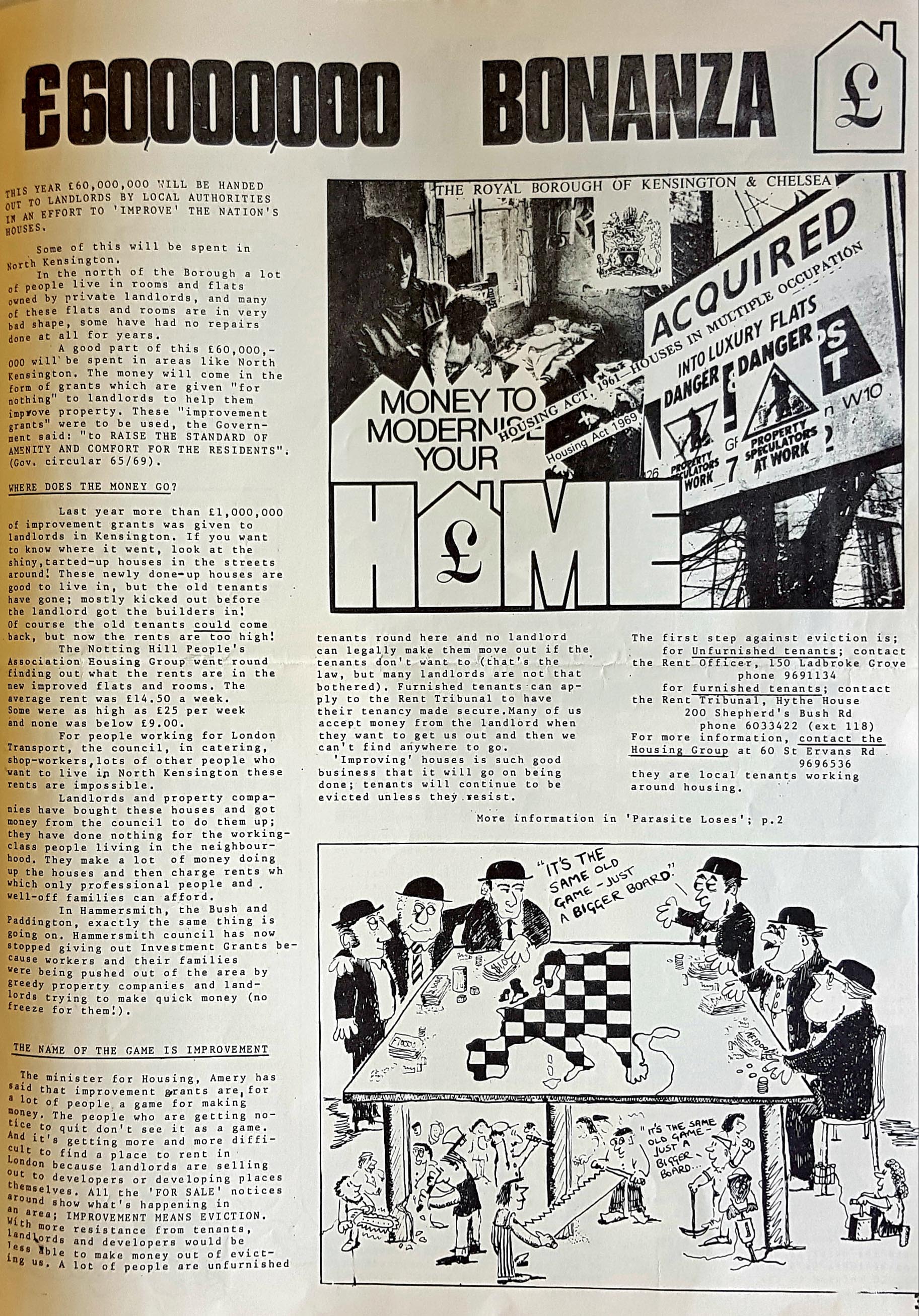

Kirkby was purchased by Liverpool Corporation as a ‘remedy’ to the large number of inner-city slums. Throughout the 1950s and 60s people were rehoused from the slums into the new properties, most of which turned out to have a number of structural problems of their own.. The Housing Finance Act of 1971 doubled the rent of properties in Kirby resulting in rent strikes lasting for over a year. LFP continued to follow the unrest.

Fast-forward to 1974, Kirkby was due to merge with Knowsley. Any money Kirkby council had not spent would automatically go to Knowsley. Kirkby Councillor, Dave Tempest, good friend of the Labour Prime Minister Harold Wilson, did not want to lose the money so opted to build a ski slope…in the middle of Kirkby…

The story was published in LFP revealing Tempest had used school children to lay the ski surface during school hours. Worse still, the ski slope was built without planning permission, on top the town’s water supply pipe, and facing a main road.

Steve Scott, who had recently joined LFP from Cambridge Evening News, delved into this scandal following an anonymous letter they received suggesting Eric Spencer Stevenson, the architect of the slope, George Leatherbarrow, the millionaire builder of the slope, and Dave Tempest were all friends; often meeting at a pub for lunch.

After a significant amount of time dedicated to studying old council minutes and following several different lines of enquiry, hard evidence for the relationship between the 3 men was uncovered. Not only were they behind the ridiculous ski slope scandal, butTempest, Stevenson, and Leatherbarrow were all scheming together and responsible for the disastrous housing in Kirkby.

Back in the mid-60s the contract for the new houses in Kirkby, including Tower Hill, lay at a whopping £4.5 million with overspending estimated at least £1 million. The council tenants of Kirkby would be paying for these houses for a very long time. Councillor Dave Tempest assured that this was because Kirkby would be getting better houses, though the LFP argued quite the opposite. Architect, Eric Spencer Stevenson, oversaw the quality of the work done on the houses and flats. He also negotiated the contract with George Leatherbarrow, the builder, and received an expensive Alfa Romeo car in return. When questioned, Stevenson denied his friendship with Leatherbarrow yet LFP went on to uncover and publish evidence of Stevenson as Leatherbarrow’s best man at his second wedding in 1973. To tie the 3 schemers to the housing crisis in Kirkby, LFP also revealed in issue 19, May-June 1975, 5 pages detailing their investigation which highlighted how building materials delivered to Tower Hill had disappeared. These materials were later found as extensions on Tempest and Stevenson’s homes, built by Leatherbarrow.

The police would then go on to carry out a long investigation, arresting the men on conspiracy charges, resulting in the imprisonment of Tempest, Stevenson and Leatherbarrow.

LFP actually sold this story to the BBC as in the midst of their investigation they kept drawing blanks and, by their shoe-string standards, had spent a lot of money on investigating and so needed a small sum to keep them going. The BBC broadcasted a film covering the story a few days after the LFP released their story. Without the groundwork of LFP and their dedicated investigative journalism, which ultimately brought down a local council, the BBC would not have been able to run the story.

LFP’s Kirkby story also had a local impact. Both the Echo and Daily Post took to tackling the issues in Kirkby following LFP’s coverage. However, the culture of these newspapers did not change, instead, they became frustrated by the presence of the LFP, particularly the attention the scandal had brought it. The editors were becoming increasingly worried about small community newspapers both stealing readers and tarnishing the reputation of the Echo.

In many ways, LFP was a product of its publishers’ distaste of the contemporary mainstream press, which was unlikely otherwise to have dedicated the time and funds to uncover a story such as the Kirkby scandal. This kind of journalism and impact was exactly what Brian Whitaker and Co had in mind when founding LFP, it’s just a shame it did not grow big enough to truly rival the mainstream newspapers.

Following the success of the Kirkby piece, from November 1975 to January 1976, the paper had a streak of appearing monthly since it first began. Unfortunately, it’s difficult to say exactly how impactful and popular LFP became because very few studies have been done on its readership and sales. However, there certainly became a buzz in the community surrounding LFP and equally the continuation of the newspaper to remain unaffiliated with any political party earnt it significant local respect.

With thanks to Mandy Vere from News From Nowhere for lending her collection of Liverpool Free Press

LFP issue 19, May-June 1975